07 Jul The Mighty Kūmara

Food and Identity

Every early crop-growing culture had its own preferred carbohydrate-rich staple food crop upon which they depended – a food that was adapted to the climate of their homelands and had been carefully cultivated through the generations. You can identify a staple food’s importance to the survival of the people because it will feature strongly in proverbs, legends, religious practices, songs, and celebrations. In fact, there is nothing like food to bring people together as a unifying source of identity. For East and Southeast Asian cultures that food is rice. For Russian and Scandinavian cultures, the potato. In England, France and much of Germany it is bread derived from various grains. And for Māori in Aotearoa, it was the humble but mighty kūmara.

The Importance of Kūmara

Kūmara was one of many food plants intentionally brought to Aotearoa on their voyaging waka by some of our forward-thinking tūpuna. However, due to the much cooler climate here, most of the other carbohydrate-rich tropical foods could not flourish. Thankfully though, the kūmara did – at least in the warmer regions of Aotearoa. This no doubt had a huge influence on where most Iwi ultimately settled. While not all of the various voyaging waka had brought kūmara with them, most of the iwi who didn’t have it, ultimately obtained it either through trade, intermarriage, or conquest, and learned the tikanga around growing it from those who were experienced in cultivating it. Because it was such an important (albeit at times, temperamental) food crop, much of the gardening practices associated with the kūmara were steeped in ceremony and ritual, with tikanga strictly adhered to, to ensure a good harvest.

In his study of Māori agricultural practices published in 1920, ethnographer Elsdon Best observed “…the kūmara stood in a class by itself, above and apart from everything else… As the mainstay of life… it was celebrated in song, and story, and proverb. Its cultivation and treatment called for the utmost care and ingenuity and were accompanied by the strictest and most elaborate religious observances.” 1

Adapting to the Climate

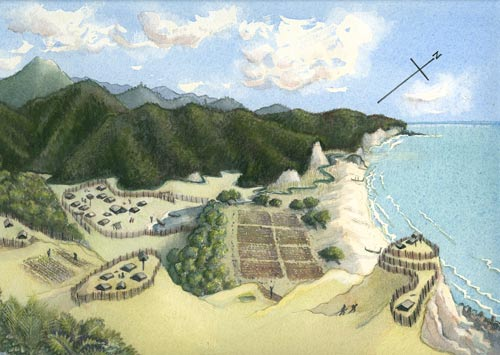

In the winterless climate of our previous tropical homelands, our tūpuna could access food all year round. The tropical forest was their storehouse. But not so in Aotearoa with its cold winter. While kūmara could be grown, it was not a year-round crop, due to frost-sensitivity. As a tuber or root crop though, kūmara stores really well, and our ancestors adapted to winter scarcity by building special reinforced, covered storage pits (rua), dug in the ground or into a hillside, where the tubers could be kept cool, pest-free, and out of the light. Evidence of ancient kūmara pits can still be found throughout the country. Our hapū kept well-stocked kūmara pits hidden high up the forest, which was where our people would retreat to during times of war. The remains of these can still be seen up in the Ōtanewainuku forest today.

Our ancestors cleverly adapted their māra (gardens) to the cooler climate by using volcanic rocks to build carefully laid-out stone walls around their crops. These acted as windbreaks and helped to warm and mulch the soil, thus extending the growing season. They also modified the soil by bringing in gravel and sand – often from long distances – to ensure good drainage and help the soil retain heat. Evidence of these huge ancient māra kai with their built stone shelter walls can still be seen today at Ōtuataua Stonefields near Ihumatao, in Auckland, and in the Wairarapa.

The Origins of the Kūmara

We know that kūmara came to Aotearoa on at least some of the migratory waka of our tūpuna, was distributed amongst the various iwi and was thus cultivated here continuously for at least 800 years. It is also found throughout Polynesia, and is known by various names similar to kūmara, such as kuumala, kuma’a, ‘umala and uala. The earliest evidence of its presence in Polynesia dates back to about 1000AD and was found on Mangaia, in the Cook Islands.2 So it has clearly been a staple food of our ancestors since way back. But where did it come from originally? Studies of genetics and linguistics tell us that like the taewa or peruperu (Māori potatoes), the kūmara is actually native to Central and South America3, where the indigenous Quechua people of the Andes have cultivated it for thousands of years – and to them it is known as cumal. We know through this that Māori and Polynesia had a definite connection to that ancient land and people.

There are other amazing pūrākau that vary from iwi to iwi about how it came here – including the East Coast legend of an ancestor named Pourangahua.4 In this pūrākau, Pourangahua embarks on a voyage in search of an unknown food for his baby son, who was always poking his tongue out seaward, to the east, as if hungry for some unknown food that lay beyond the sea. So, like any doting Dad, he headed out into the moana to find it, eventually making landfall on an island where the welcoming inhabitants offered him a strange new food called kūmara, to eat. On tasting it, he knew he had found what he was searching for. He stayed for a while there as a guest of the people and their priest, Tāne, but soon began to long for home and family. With his waka somehow lost, he was fortunately able to borrow Tāne’s giant manu to return home with the prized kūmara tubers, after promising to follow strict instructions for how to care for the bird. However, in his haste to see his family again, Pourangahua neglected to take care of the giant manu to ensure its safe return, and as a result it soon came to a grisly end. When learning of his pet’s demise, the priest responded to Pourangahua’s carelessness and neglect by sending three diseases to attack his kūmara crops. So, according to this kōrero, thanks to Pourangahua we may have the kūmara, but as a result of his neglect and unkindness we would always have to work hard to cultivate it, and it would not always flourish.

The Modern Day Kūmara

Once a distinctly Māori food, kūmara is now regularly eaten by most New Zealanders. With tubers much larger than the kūmara our tūpuna first brought to Aotearoa, it also comes in a wider range of colours and varieties. Due to its excellent storage ability, it is a source of carbohydrate that is generally available in the supermarket all year round. Most kūmara you can buy in the supermarkets nationwide are grown in the winterless North with its fertile soils and warmer climate. In our whānau though, we still prefer homegrown kūmara, from right here in Tauranga Moana, as there is nothing as satisfying as being able to enjoy the fruits of your own labour.

NUTRITIONAL BENEFITS

While potato is used much more widely in today’s food products, and its taste preferred by many (including my own family), nutritionally, the kūmara is, in some ways, superior. It contains more dietary fibre and complex carbohydrates per gram than the potato. It also has a lower glycaemic index than potato, despite its sweeter taste – which means the energy derived from kūmara will sustain you for longer. While actual nutritional content will always depend on the variety of kūmara you are eating, where it is grown and how it is prepared, the range of micronutrients it is likely to contain includes vitamins A, C, E, and most of the B vitamins, as well as potassium, calcium, copper, iron, manganese, and magnesium. The skin and flesh of the more colourful red/orange and purple-fleshed varieties also contain health-protective antioxidants such as beta-carotene and anthocyanins. To ensure these and other nutrients are made available, it is best to cook and eat kūmara with the skin on. Even the kūmara leaves are also edible and can be used just like spinach or added to soups and stews. As another source of leafy greens, the leaves contain antioxidants, plant protein, folic acid, iron, potassium, and vitamins C, K and D.

Mighty and Nourishing

Just as our tūpuna did, there are a great many ways to enjoy this health-giving food. As per tradition, it is often added to soups, stews, and boil-ups. It can be boiled and mashed, stuffed, cut up and roasted with meat, or made into wedges. If you are lucky enough to get your hands on a steam-cooked hāngi, kūmara will undoubtedly feature in it. It can also be cooked and enjoyed cold, in a salad. Nowadays there are many non-traditional dishes kūmara will feature in, with a wide range of interesting recipes easily accessible on supermarket stands or on the internet – including our website! So, if you don’t already, go ahead and take the opportunity to enjoy the nourishment the mighty kūmara can offer you and your whānau this winter!

References

1. McLauchlan, G. 2018. NZ Gardener, June 16. Māori horticulture: growing kūmara and other crops the traditional way. https://www.stuff.co.nz/life-style/homed/garden/104307657/mori-horticulture-growing-kmara–other-crops-the-traditional-way

2. Harburg, J. 2014. Cumal to Kūmara: The voyage of the sweet potato across the Pacific. Hohonu, 12. University of Hawai’i at Hilo. https://hilo.hawaii.edu/campuscenter/hohonu/volumes/documents/CumaltoKūmara-TheVoyageoftheSweetPotatoAcrossthePacificJennaHarburg.pdf

3. Ibid.

4. Te Ao Hou, Dec 1962. How the kūmara came to New Zealand. National Library of New Zealand. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/TAH196212.2.22