07 Jul Mānawatia a Matariki

In pre-European times, our ancestors lived their lives in tune with the environment, carefully watching the heavens and the changing seasons to help regulate their lives. In many parts of Aotearoa, the first new moon after the re-appearance in the early morning sky of the Matariki cluster of stars (the Pleiades constellation) ushered in the Māori new year.

Te wā o Matariki (the season of Matariki) was an important time of year. It was a time to reflect on what had been achieved over the past year, a time to plan for the year ahead, a time to gather together, celebrate, and enjoy the bounties of the harvest. A time to share kai and kōrero, to remember tūpuna and loved ones, and to give thanks.

MATARIKI ME TE TAIĀO

Today, not only does the advent of Matariki remind us of whakapapa connections to past, present, and future generations of our whānau, it can also help to reinforce the importance of our connection to te taiāo (the natural environment) and to the traditional food sources our ancestors would have harvested from its domains. This connection was pretty vital given that the survival of the people depended on being able to protect, conserve, and maintain the food sources that were available to them. Food was (and still is) a huge part of the traditional rituals and celebrations held during this time. In fact, each visible star of the Matariki cluster represented a particular aspect within te taiao, with many of them associated with food.

How each individual star looked when Matariki first reappeared in Pīpiri (June-July) indicated what our tūpuna might expect in terms of being able to harvest from those food sources in the coming year.

Also, how Matariki appeared as a cluster would also indicate to our tūpuna master gardeners what kind of winter was ahead and when to begin planting again. If it appeared hazy, with the stars bunched close together it would be a long, cold winter and planting should be delayed until around Whiringa-ā-Nuku (September-October). However, if the stars twinkled bright and clear, it would be a good growing year ahead and planting could begin in earnest in Mahuru (August-September).

When Matariki set in the west, near the end of the year, during Haratua (April-May), this signalled to our tūpuna that harvesting time was over and it was time to prepare for the cold months ahead – as indicated in the whakatauki ‘Hauhake tū, ka tō Matariki’ – the harvest ends when Matariki sets’.

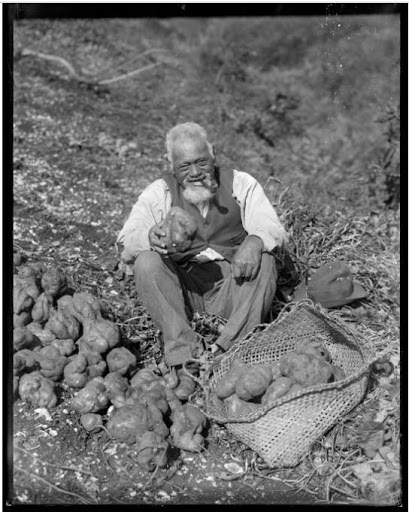

Another whakatauki ‘Matariki ahunga nui’ – ‘The great mounds of Matariki’ – gives us a great visual of the kūmara (and other foods) that had been harvested and piled up, ready to share out amongst the whānau, or be stored for future use, especially during winter.

A TIME TO REFLECT… AND PLAN AHEAD

As our tūpuna looked upon the harvested bounties before them, perhaps they would reflect on what had happened over the past year, and what could be learned – such as what worked and what didn’t, and possible reasons why. They might have considered what they would do differently, if anything, in the coming year, to ensure a better harvest and plenty of stores over winter, so that their hapū could continue to thrive.

Te wā o Matariki is also a great time for those of us living today to also consider our own food security. Do we have sufficient food stores set aside for our whānau in case the unexpected happens? How long would we last if we could no longer just pop down to the shop? Memories of supermarket shelves starkly empty of such staples as flour and sugar that occurred frequently over the COVID lockdown last year immediately spring to mind. A pertinent question to ask at this time then, is what are we doing to prepare ourselves food-wise, for an uncertain future? How prepared would we be if another worldwide catastrophe were to say, suddenly disrupt the food supply indefinitely? Or what if a job loss and its resulting reduced income were to suddenly hit close to home?

GET YOUR GARDEN GROWING!

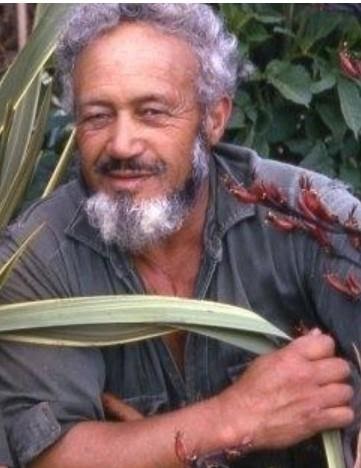

One thing we can do to be a little more prepared, is to have our own vegetable garden and fruit trees growing on our property. If yours wasn’t one of the many New Zealand families who decided to get their green thumbs to work during lockdown last year, why not plan to do so this year? This wintery Matariki season would be a great time to start learning what to do and begin gathering resources and preparing soil in time for Spring. Even if we are living in an apartment in the city with limited outdoor space, or living in a colder area, or are renting and unable to put in a garden – with a bit of thought, time, effort, and kiwi ingenuity, it is possible for anyone in Aotearoa who is motivated enough, to start growing their own food.

There are SO many great reasons to grow your own food: the opportunity to reconnect with nature, with the whenua, and with people in the community; the obvious health benefits of eating fresh, organic food; being able to control what is, and what is not going into that food (such as fertilisers, and pesticides); having better food security for your family; developing practical skills; and the pride and satisfaction of being able to enjoy the fruits of your own labour. There are also some great, free resources within our local communities, the support of gardening groups on Facebook and other internet sites that give free advice for people just starting out, or on a budget.

MEMORIES OF TŪPUNA AND OUR MĀRA KŪMARA

For my whānau, another great reason for growing our own kai, and especially kūmara, is the special connection it gives us to our tūpuna who have gone on before. Te wā o Matariki is a great time to acknowledge them and give thanks for such a wonderful heritage.

I remember as a child, our whānau traveling back to Tauranga often during the school holidays from wherever we happened to live at the time. Dad would have us spend many long hours, toiling in the dirt under the hot sun, either in Nanny’s or in Grandad’s huge gardens, weeding seemingly endless rows and rows of kumara, potatoes, corn, and other vegetables.

Despite all the hard work, my older sisters and I have good memories of the times we got to spend with Grandad in the garden, as he entertained us with hilarious tall tales while we worked. His eyes always twinkled with mischief to match his cheeky grin whenever he cracked a joke. I remember the tiny little roadside stall he had at the beginning of the long dirt track to his house, from which he would sell some of his home-grown produce. I’m not sure if he made much money selling his produce that way, but I do know that he was a kind and generous man despite his own humble circumstances and was well-respected in the community.

He would often load up his old haratētē car with crates full of fruit and vegetables that he’d grown, to give to extended whānau or friends in need. With Grandad, as with many of that generation, the concept of manaakitanga (caring for others) and the tradition of sharing the bounties of the harvest communally always remained strong.

Our great-grandmother Nanny Hinetu was the same. Whenever we visited, she would wail and cry as she hugged us close and ushered us into her humble whare, (whilst also growling Dad for not bringing us to see her more often). She would then immediately start to prepare food to feed us, whether it be boil-up or stew made with veges from her garden, shellfish, or eggs from her chickens, or fresh, hot takakau or fried bread which we would eat, smothered with her homemade jam. Later on, in the gardens, I remember watching her as she worked. For all her many years, she was spritely and fit and could out-weed all of us, no trouble.

Though we didn’t enjoy the hard manual labour in the gardens alongside our parents and tūpuna as kids, we certainly did enjoy eating the produce that was able to be harvested as a result. We never went hungry. And now, we all know how to grow, harvest, and preserve our own produce, to nourish our families just as they did. We will always be grateful for this sweet legacy and the knowledge that has been instilled in us, through the teaching and examples of our parents and grandparents.

Just as Dad did with us, we have also regularly brought our children back to our parents’ homestead in Tauranga and given them the opportunity to make their own memories, working in the garden alongside Nanny and Koro – and yes, in the hot sun too (- but just for a few hours)! They also regularly get to enjoy the bounties of the harvest as well. I’m sure they probably don’t fully appreciate the value of making these memories with their grandparents just yet, but hopefully as a result of what they learn, growing their own kai will be a practice of the next generation also – as a principle of self-reliance, to ensure their own food security, exercise a bit of tino rangatiratanga over their own lives, and especially, to maintain their physical and spiritual connection to the whenua and their tūpuna. The world has changed dramatically since our childhood days, as has our hometown. With the encroachment of more highways and the explosion of townhouses being built everywhere for the burgeoning population of Tauranga, the size of our whānau lands and gardens have greatly reduced. Nanny’s long-drop, the old, dirt roadway to Grandad’s house and his tiny, covered roadside stall that once sat at the road entrance are all long gone now, as are they.

And last year, just before lockdown, our Dad also left us to join his parents and whānau kei tua i te ārai (beyond the veil). So now it is up to us to maintain this whenua and the horticultural traditions that have been passed down, to nourish the soil so it will nourish us, and especially to continue the cultivation of kūmara here on our land, hopefully for many generations to come. Even more so now, the act of gardening, and especially of growing kūmara, evokes a bittersweet reminder of our Dad, Grandad, Nanny and all those who have done the same here for years before us. For us, the kūmara is not just a vegetable and cultivating it, is not just a chore. It is a special part of our heritage – a practice and a plant whose long, leafy branches and reaching tendrils bind the many generations of our whānau – past, present and future.